Angelo's Saturdays

High School: Grades 9–12

Story

Angelo's Saturdays

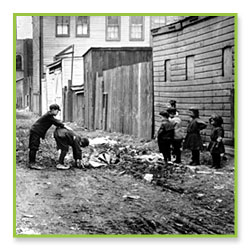

On tiptoes, Angelo looked out the window with his nose pressed against the windowpane. Although it was summer and the humidity seemed to drape over his skin like a wet wool blanket, the window was closed. Looking down three stories into the unpaved alley, he could see the top of the wooden privy 1 that was propped up against the building. All the tenants who lived in Angelo's building used this privy—there were no toilets in the building itself because it was not connected to the city sewer system. If the building's tenants were fortunate (especially the families who lived in the back), the owner of the building might hire a scavenger service to empty it out. Otherwise the contents of the privy (as well as the neighboring ones) continued to fester in the humid August air. The stench hung day and night; keeping the window closed barely kept the fetid air at bay—especially after it rained, when the contents of the privies would overflow and seep slowly into the dirt floor alley. When summer first arrived, Angelo thought he might throw up from the smell, but he had gotten used to it, along with the other squalid living conditions on the Near West Side of Chicago.

The year was 1898 and the 19th Ward, where Angelo's family had settled, was home to thousands of Eastern and Southern European immigrants.

After surveying the alley, Angelo looked southeast out over rooftops and daydreamed what it would be like to be rich in this city. His friend, Vito Gentile, who also lived in the tenement, told him that not all neighborhoods in the city were like this: rich people actually lived in Chicago, too. Vito had tried to teach him the names of some of the most famous families: "the McCormicks, the Palmers, the Marshall Fields..." Vito told Angelo that many rich people lived in huge mansions only a few miles away.

"You see, Angelo," Vito said with a mischievous grin, "if you learn to read and write English, maybe you can be a rich, fat man who lives on Prairie Avenue in a house that has a bathroom with a toilet."

Such comments frustrated Angelo. Vito was going to a brand new school, Gladstone Elementary, only a few blocks away. Vito was the youngest of four; since his older siblings were all working, he was able to go to school. Angelo, on the other hand, was the eldest son, and his family desperately needed the money he made from selling newspapers. The $1.00 he brought home each week was about 25 percent of their income.

As was common in immigrant neighborhoods, people from the same villages frequently lived near each other; both Angelo and Vito's families had come from Vallelunga, Sicily. But Vito now had other friends at school and his command of English surpassed, "My name is Angelo Blandino." Angelo felt increasingly frustrated.

Downloads (pdf)