Both the editor of the Libby Prison Chronicle and the museum manager were required to make financial investments in these enterprises. John Ransom advertised for a successor to invest in the Chronicle when he assumed the position of museum manager in November 1894:

An Opening for the Right Party

The editor of the Chronicle has leased the Libby Prison War Museum and his duties are many...There is a brilliant future in store for the paper if properly managed, just as the editor thought there would be when he started it, but he has now more on hand than he can well attend to. He wants a comrade to come to the rescue and take charge of it...Every facility will be granted by the Libby Prison War Museum to encourage the enterprise. The whole outfit or a portion of it will be sold to the right party. Not much money is required. The main thing is to have the paper in good hands...It is the only strictly ex-prisoner of war paper published in the United States and with proper management can be made a permanent success.

Civil War soldiers and prisoners returned to Chicago after the war to participate in a period of unprecedented economic growth.

Many privates enrolled in commercial colleges to become business clerks. Officers were lured by the expanding insurance industry that protected increasing capital investments. High ranking officers filled the top positions in several new companies that emerged after 1865. Former soldiers voted for veterans at election time -- a Republican slate of veterans was swept into office in 1867. (KARAMANSKI 242)

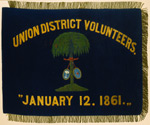

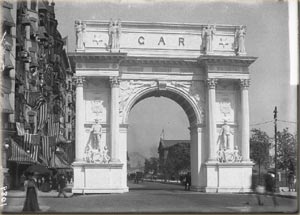

Veterans organizations became popular in the late 1870s. Membership in the Grand Army of the Republic, the largest veteran group, grew substantially in the 1880s along with several other military associations. Father Abraham was idealized as a symbol of compassion, individualism, and social responsibility that was increasingly at odds with Chicago's political and economic climate. (KARAMANSKI 243)

The Libby Prison War Museum became a national center for Civil War veterans and former prisoners.

The museum sponsored veterans reunions, and Gunther arranged for reduced train fares for out-of-state attendees. The Libby Prison Chronicle was published by John Ransom, inmate of Belle Isle and Andersonville, for two years following the museum's 1894 attendance peak:

The Libby Prison Chronicle is a paper published at Libby Prison in the interests of ex-prisoners of war and particularly those who were confined in Libby, by comrade John L. Ransom, present manager of Libby, who was himself a prisoner of war for fourteen months...The publication is a...continuation (after thirty years) of the old and original Libby Chronicle...within the walls of Libby at Richmond, VA...The Libby Prison Chronicle is the only paper devoted exclusively to ex-prisoners of war.

Veterans prized their jobs as guides at the Libby Prison War Museum.

A dismissed guide wrote a letter to the museum manager in 1890 begging to be reinstated, and offering to work without pay:

Dear Comrade,

The veterans established a Military Cadet, Fife, Drum, and Bugle School at the museum.

It is proposed by LeRoy Van Horn and Major John Catlin, both musicians well known in Chicago...to establish a school of learning and preparatory branch of music, where boys between the ages of nine and fourteen years may receive instruction on the fife, drum or bugle, and cultivate the talent best suited to them...Hours for lessons are from 10-11 and 2-3 every day except Sunday. First 6 lessons free, then each lesson 10cents. (LP CHRONICLE, August 1894)

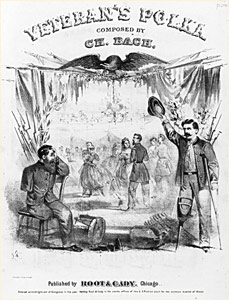

"Veteran's Polka," George Root, 1869 (ICHi-31106); "The Boys of Chicago," Libby Prison Chronicle, August 1894 (ICHi-31093).

I hope you will excuse me for writing these few lines thus intruding on your time. My being retired from my place in Libby was so unexpected that I feel I have been unjustly dealt with...I don't blame you...I think it was through the misapprehension of some other parties. They thought I was too old there is but a year or two between me and Mr. Foster and I know I can explain as well as he can and get about as well...I was in to hear the new man and if I can't explain twice as much as he did I will give you my services for nothing. (HARPER)

"Old Soldier's Home," A.T. Andreas, History of Chicago, vol.2, 1885 (ICHi-31105).